Exposing the Myths of Australia's Ivermectin Restrictions

Debunking the myth of ivermectin shortages and public health risks from allegedly increased "off-label" ivermectin prescribing in 2021.

On 10 September 2021, Australia’s drug regulator, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) imposed a ban on general practitioners prescribing ivermectin for “off-label” uses.

In a decision reminiscent of its hydroxychloroquine restrictions in March 2020, the TGA cited concerns of safety risks and shortages in making this decision. Yet, as our investigation in this article reveals, these concerns about ivermectin’s safety were unfounded and relied on seriously exaggerated threats of shortages.

We therefore conclude that the restriction of ivermectin access had little to do with patient safety or supply integrity. Rather, it functioned as a coercive public-health sanction, explicitly designed to penalise non-compliance and ambitiously drive COVID-19 “vaccination” uptake.

What is “off-label” prescribing?

A critical distinction must be made, one that has consistently been blurred in both the TGA’s reasoning and subsequent media reporting; “off-label” prescribing and “private” prescribing are not synonymous.

“Off-label” refers to how a medicine is used relative to its approved indication; “private” refers to how that medicine is funded. An off-label prescription can still be Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme-subsidised (PBS) if it meets the PBS restriction criteria, while a private prescription, whether on-label or off-label, is never PBS-subsidised.

This distinction matters because the publicly available prescribing data, published by Australia’s PBS, captures dispensing, not clinical intent. A claim of a surge in “off-label” prescribing in 2021 required either a corresponding increase in PBS-subsidised dispensing, or widespread private prescribing at the height of professional intimidation, regulatory threats, and media vilification.

As we reveal in this article, there was no substantial increase in ivermectin prescribing and it was implausible that private prescribing surged in Australia at this time too.

Manufacturing consent

It all started so well for ivermectin.

But by 2021, the story had very much changed.

Before the TGA announced its ban on “off-label” ivermectin prescribing, the legacy media was flooded with slurry-grade propaganda slop, conditioning public acceptance and pre-assembling the soundbites needed to make the decision appear inevitable:

The function of these stories was not to impartially inform the public, but to manufacture consent on behalf of the TGA, even if these stories contained obvious disinformation. For example, that a man was hospitalised following an ivermectin overdose.

It simply didn’t occur.

Bizarrely, The Guardian article headline (below) claimed it occurred, even though in the second paragraph of the article we learned that it was not an ivermectin overdose at all:

Yet, the fake claim about the overdose was circulated in many other stories as though it was factual.

It was included in The Conversation article, authored by three academics from the University of Sydney:

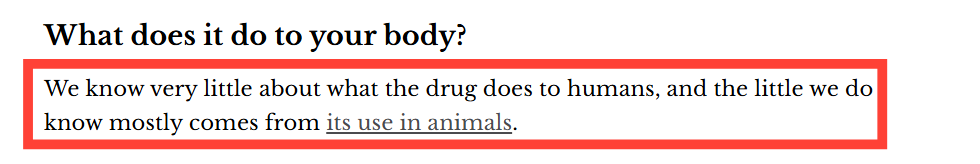

Despite their credentials and pharmacy expertise, the authors astoundingly confessed to having little knowledge of what the “controversial drug” did to humans:

Yet, as these experts must surely have known, ivermectin has been used in humans for decades, with billions of doses administered worldwide, particularly through mass drug administration programmes for onchocerciasis (river blindness) and strongyloidiasis (threadworm). Its pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, metabolism, dosing ranges, contraindications, and adverse-event profile are all understood in humans.1 The medicine has an extensive regulatory history, including Nobel-Prize-recognised impact, and is listed on the WHO Essential Medicines List.

The article portrayed ivermectin as an obscure or experimental drug, seriously undermining the scientific credibility of the authors and their claims about this “controversial drug”.

It was a hit job by the legacy media on ivermectin which was completed in a matter of roughly ten days.

The TGA decision

With the pre-programming complete, the TGA convened an emergency meeting of the Advisory Committee on Medicines (ACMS) to provide advice about what to do with ivermectin.

The ACMS advice to the TGA, later released under FOI, revealed the Committee’s concerns about risk-taking behaviour of “unvaccinated” ivermectin-users who might have believed themselves to be protected from the disease and therefore, would have decided not to get “vaccinated” as part of the national “vaccination” program, or sought appropriate medical care if they developed symptoms of COVID-19, therefore creating an infection risk in the community.

The ACMS also noted the spread of misinformation regarding the appropriate, safe and “well-tolerated” dosages of ivermectin and the risks, including death, this created for “unvaccinated” ivermectin-users.

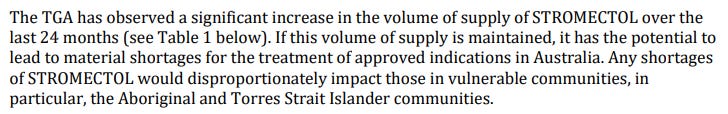

A related concern was how increased “off-label” prescribing could create medicine shortages, particularly for vulnerable communities like Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders who were more prone to diseases for which ivermectin was indicated.

Despite providing no evidentiary support beyond its assertions of public health risks from the “unvaccinated” bingeing on horse-paste in toxic dosages, wandering the streets infecting all and sundry, the ACMS advice was accepted by the TGA and the restrictions were imposed.

The public health risks

The public health risks posed by ivermectin were based on several fanciful assumptions:

People who sought and used ivermectin for prophylaxis or treatment of COVID-19 disease would consider getting “vaccinated” if ivermectin availability was restricted;

“Unvaccinated” ivermectin-users were a greater infection risk to the community than the COVID-19 “vaccinated” because they would think they were protected from COVID-19 and would not engage in protective health measures;

“Unvaccinated” ivermectin-users would not seek “appropriate medical care” if they developed symptoms of COVID-19; and,

Dangerous misinformation was exposing potential ivermectin-users to risks, including death from a medicine that could cause serious illness and death.

Let’s address these one-by-one.

First, the types of people resilient enough to have resisted mandates, relentless legacy media propaganda, societal pressure, and enduring lockdowns to be “vaccinated”, it can be said with near certainty, were not your prime candidates for “vaccination” with any COVID-19 “vaccine” whether or not ivermectin was or was not available. The idea that these individuals would run down to their local pharmacy to roll up their sleeves if ivermectin was restricted was plainly stupid.

Second, as was known even at the time in September 2021, “vaccination” did not prevent infection with SARS-CoV-2, so those “vaccinated” with COVID-19 “vaccines” were an even greater infection risk to the community as the “vaccinated” were proportionally a much larger cohort at the time. These matters aside, most of the country was still living under oppressive lockdown regimes where movement was highly restricted. The idea that “unvaccinated” ivermectin-users could and would threaten the “vaccinated” failed to take into account these enduring lockdowns and it also rehashed the absurd fallacy of “my ‘vaccine’ won’t work if you’re not ‘vaccinated’ too”.

Third, it was a mere assertion that ivermectin users would avoid seeking medical care if they developed COVID-19 symptoms. Yet, on balance, if this assertion were true, could you blame them? Pause to reflect on what constituted “appropriate medical care” in 2021 for the treatment of COVID-19. Wait at home until you’re sufficiently sick and gasping for breath, then come to hospital to be intubated and denied antibiotics to suffer bacterial pneumonia? No thanks. Consider also, how these protocols differed according to your “vaccination” status. The National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce protocols at the time — and long afterwards too — prioritised remdesivir (“run death is near”) only for “unvaccinated” COVID-19 patients to prevent hospitalisation based on the flimsy likelihood (one clinical trial only) that it “probably” reduced the incidence of hospitalisation in patients if it was started within seven days of symptom onset.2 If “unvaccinated” ivermectin-using individuals avoided health establishments in 2021, it was a well-informed choice at a time where the nature of care provided exclusively to them was punitive and potentially lethal.

Fourth, since the pandemic commenced, Australia’s Database of Adverse Event Notifications (DAEN) has recorded only one adverse event report involving death from ivermectin as a suspected medicine (sadly, in a case report involving a cocktail of other suspected medicines including fentanyl). As one the World Health Organisation’s essential medicines, the safety profile of ivermectin has already been well-established. Had the TGA actually been concerned with the proper dosing of ivermectin, then restricting general practitioners from prescribing the essential medicine would have only increased the potential for individuals to have mistakenly consumed improper, potentially toxic doses of ivermectin. That is, if the TGA claim about misinformation and dosages is to believed without evidence; which it should not be.

For the above reasons, we doubt the restrictions on ivermectin had anything to do with public health risks, leaving only the possibility that it was about shortages.

Shortages

Prior to its decision, the TGA had reportedly observed significant increase in the volume of supply of ivermectin, which allegedly amounted to “3-4-fold increased dispensing of ivermectin prescriptions in recent months”:

However, the claim was never substantiated and we cannot independently verify the TGA’s claims until the TGA chooses to disclose its source data and/or unredact “Table 1” as shown above.

If the 2021 surge in ivermectin use had genuinely occurred through “off-label” prescribing, it should have appeared in PBS dispensing data, but there was only subtle month-to-month changes in ivermectin prescribing at all in the months prior to the decision:

The claim of “300-400% increase” in prescribing was evidently false and there clearly was not a “sustained increase over the last 24 months” to September 2021, as claimed. This implies that the surge never existed, or that the TGA is asking us to believe in a mass of covert private prescribing which would not be recorded in the PBS data.

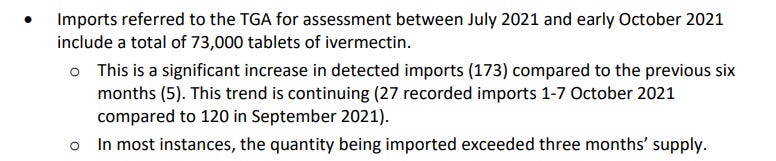

Another strong reason for doubting the TGA’s intervention was driven by its fear of ivermectin shortages is that Australia was reportedly flush with imported ivermectin at the time. Information released under FOI by the TGA show how personal imports of ivermectin in the period from July-October 2021 had significantly increased:

If individuals could obtain ivermectin freely and easily locally from general practitioners, then personal imports would have been costly and redundant. Surges in imports of ivermectin indicate that ivermectin was plausibly very hard to come by. Most doctors were “vaccine”-pushers and most doctors still are. Therefore, the TGA’s claim about surges in “off-label” prescribing — which it presumably conflated with “private prescribing” — is implausible.

In sum, the TGA’s claim that it was concerned with potential shortages for ivermectin is contradicted by its own evidence that Australia was awash with imported and locally sourced ivermectin at the time.

Economics 101

The concerns about medicine shortages also seriously miss the point.

Simple economics dictates that a shortage of a product sends a market signal to producers to increase the supply of the product. In the short-term, such a shortage can even raise prices until supply is increased and prices return to their normal equilibrium level.

It is unclear how or why the TGA considered that a shortage of a low-cost, generic medicine that could be manufactured at scale could not have been overcome.

Though one shortage for ivermectin occurred on 2 August 2021, driven by “unexpected consumer demand”, it was resolved a mere 18 days later on 20 August 2021.

Clearing the market of excess demand in this way (i.e. alleviating the shortage) had nothing to do with swift regulatory action, it simply represented the regular functioning of the market economy.

In proof of this proposition, to date, no further shortage of ivermectin has been recorded.3

And this is despite Australia’s burgeoning appetite for ivermectin.

Australians want ivermectin

It was not until June 2023 that the ban on “off-label” prescribing was lifted by the TGA, as it was satisfied that the public health risks of COVID-19 had been mitigated by “vaccination” (piggybacking once again on natural immunity) and the encouraging supply data of ivermectin.4

As it turned out, it was essential that the supply data was encouraging, because Australians really want ivermectin.

Lots of in fact.

The trend in prescribing in this period is quite remarkable:

(The above graph is interactive. If you are reading this article in your email, click to open the graph in its own window to enable interactivity.)

It should be noted that these data reveal actual dispensing (including repeats) of ivermectin, not solely the issue of prescriptions, and so, the graph shows the number of actual medicines obtained by individuals and used (or perhaps stockpiled in anticipation of our promised next pandemic).

What could explain the soaring increase in ivermectin prescribing?

You could ask Google that question…

But, we’re probably past the point of trusting Big Tech now aren’t we?

So, we put forward two possibilities that could explain the ivermectin prescribing trend shown.

Either:

Australia has been experiencing a silent, multi-year epidemic of scabies, threadworm and river blindness that has left no trace anywhere else in the health system.

Or:

Doctors have increasingly been issuing PBS-subsidised prescriptions for ivermectin for “off-label” purposes.

We think it might be the latter.

The remarkable story is not even fully captured in the above graph.

To create the graph we bundled both PBS codes for ivermectin together to show “Total Ivermectin Prescriptions” in the period. But ivermectin issued under PBS code 2688Y provides double the ivermectin (8 tablets) compared with PBS code 8359Y (4 tablets) and it is the double dosage that is responsible for the absolute majority of prescribing increase:

Australia is truly now awash with ivermectin to a level not seen before in its prescribing history.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated that the TGA’s intervention on 10 September 2021, was not based on concerns of safety and shortages from substantial increases in “off-label” prescribing.

The data show substantial increases in prescribing did not occur, certainly not to the 300-400% level claimed by the TGA.

Remarkably, the near-1000% increase in prescribing of ivermectin today has prompted neither the same concerns or intervention from the TGA, nor caused any shortages of the medicine.

We have shown how substantial increases in personal imports of ivermectin were indicators that ivermectin was difficult to obtain domestically, discrediting the suggestion that there could have been substantially increased private prescribing of ivermectin at the time.

Whatever the cause, the data for ivermectin prescribing to June 2025 shows a seismic shift in the thinking by health professionals which, hypothetically, could be for the treatment of COVID-19 but perhaps something else, such as its potential anti-cancer properties.

The post-2023 surge in PBS-dispensed ivermectin strongly suggests that “off-label” use, now freed from regulatory sanction, is occurring within the PBS framework, not outside it.

The change is not only an increased demand for ivermectin, but also in doctors’ willingness to prescribe it openly, and that is a welcome shift from the dogmatic thinking around COVID-19 “vaccines” and ivermectin that must be occurring in many more health professionals today.

González Canga, A., Sahagún Prieto, A. M., Diez Liébana, M. J., Fernández Martínez, N., Sierra Vega, M., & García Vieitez, J. J., “The Pharmacokinetics and Interactions of Ivermectin in Humans — A Mini-Review”, The AAPS Journal, 10(1), 2008, 42–46.

Peña-Silva, R., Duffull, S. B., Steer, A. C., Jaramillo-Rincon, S. X., Gwee, A., & Zhu, X, “Pharmacokinetic Considerations on the Repurposing of Ivermectin for Treatment of COVID-19”, British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 87(3), 2021, 1589–1590. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.14476

National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce, “Australian Guidelines for the Clinical Care of People with COVID-19”, https://files.magicapp.org/guideline/0b4c8c7d-f57c-4524-b60d-e690ff0b4452/published_guideline_7252-74_1.pdf, p. 212.

The certainty of this evidence was described as “moderate” even though it was based on one solitary clinical trial and the evidence from the clinical trial revealed other serious dangers with remdesivir.

TGA, “Medicine Shortage Reports Database”, https://apps.tga.gov.au/Prod/msi/search?shortagetype=All&exportType=CSVExportArchive, line 2724. For up-to-date statistics, visit https://apps.tga.gov.au/Prod/msi/search?shortagetype=All&exportType=Excel and search for “Ivermectin” or “Stromectol” - both return zero results.

TGA, “Notice of Final Decisions to Amend (or Not Amend) the Current Poisons Standard”, 2.2, https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-05/notice-of-final-decision-to-amend-or-not-amend-the-current-poisons-standard-acms-40-accs-34-joint-acms-accs-32.pdf, pp. 15-19.